Journey to Freedom

The heroic story of an enslaved man who planned a daring escape to freedom and who spent the rest of his life tirelessly working for equality.

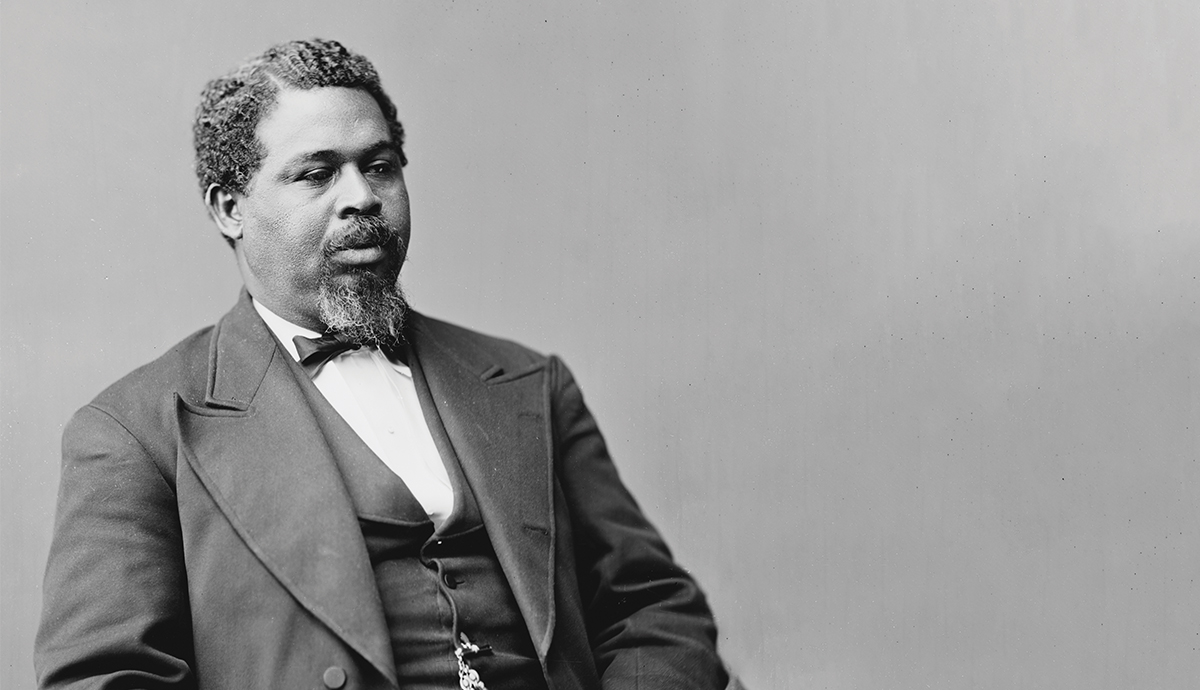

“My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.” These eloquent words were spoken by Robert Smalls in 1895 and are emblazoned on a monument to him in a quiet cemetery in Beaufort, South Carolina.

Robert Smalls was born enslaved in Beaufort County, South Carolina, in 1839 on the grounds of his enslaver’s townhouse at 511 Prince Street. Smalls’s mother, Lydia, worked in the big house, and his father might have been his enslaver, Henry McKee, or possibly plantation overseer Patrick Smalls. McKee owned a large plantation, but Smalls was not a field hand. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. notes, “The McKee family favored Robert Smalls over the other slave children, so much so that his mother worried he would reach manhood without grasping the horrors of the institution into which he was born. To educate him, she arranged for him to be sent into the fields to work and watch slaves at ‘the whipping post.’”

Smalls was a defiant young man, and, at age twelve, McKee sent him to Charleston at the request of his mother to be “hired out,” finding employment and sending most of his proceeds home. Smalls labored as a waiter, lamplighter, and stevedore. He married an enslaved woman named Hannah, and Hannah’s owner agreed to let him buy her and their children outright.

Smalls began slowly saving the seemingly unattainable eight hundred dollars he would need to permanently unite and free his family. He showed maritime talent, working as a sailmaker, rigger, longshoreman, wheelman, and ultimately a pilot. Smalls gained intimate knowledge of the depths and sounds of Charleston Harbor and its treacherous sandbars, making him a valuable captain—and giving him a key tool that would help him gain his freedom.

Civil War Comes to South Carolina

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union. A few months later, the American Civil War began in earnest when the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter in the Charleston Harbor. The fort fell to the Confederacy, and the Union blockaded the harbor in hopes of eventually seizing Charleston, the “cradle of secession.” The Confederacy outfitted their own naval fleet, including the CSS Planter, a steamer with a paddle wheel and wide wooden deck. It had begun cruising in 1860 as part of a steam packet line, transporting bales of cotton from the Pee Dee and Charleston to Boston. The Confederacy impressed the Planter, and it became a blockade runner and transport vessel, heavily armed for making supply deliveries to various nearby Confederate coastal defenses.

Robert Smalls became a trusted member of the Planter’s crew. Despite his reputation as a skilled pilot, Confederate forces would never give this title to an enslaved crewman and he served under Captain Charles J. Relyea.

Smalls Steals the Planter

Before sunrise on May 13, 1862, Smalls saw his chance. Captain Relyea and his fellow officers retired for the night, leaving the enslaved crew in charge of the Planter, which was stocked with ammunition, a pivot gun, a howitzer, and several other long-range weapons. In Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls’ Escape from Slavery to Union Hero, author Cate Lineberry explains the palpable fear and tension of contemplating escape in the slave-holding South, on a Confederate ship no less: “In the next few hours, Smalls and his young family would either find freedom from slavery or face certain death. The only way Smalls could ensure that his family would stay together was to escape slavery. This truth had occupied his mind for years as he searched for a plan with some chance of succeeding.”

Wearing Captain Relyea’s hat as a disguise, Smalls piloted the Planter to pick up his and his shipmates’ enslaved families at Atlantic Wharf, and then the party headed out to Charleston Harbor.

Smalls seized his chance to steal the unmanned boat, with the help of two enslaved shipmates. Wearing Captain Relyea’s hat as a disguise, Smalls piloted the Planter to pick up his and his shipmates’ enslaved families at Atlantic Wharf, and then the party headed out to Charleston Harbor. The Planter cruised stealthily past heavily gunned Confederate batteries and Fort Sumter. Smalls knew the right signals to flash at the Confederate checkpoints, which were none the wiser that Smalls was captain as he sailed to the ocean, past Fort Sumter, and onward to the Union fleet that was blockading the mouth of the harbor. As he neared the blockade, Smalls ordered the Palmetto and Confederate flags to be lowered. In a tense moment, the blockade fired on the Planter, not seeing the white flag Smalls had hoisted.

Historian James McPherson quoted a Union witness’s account of the exchange: “Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, ‘I see something that looks like a white flag’; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and ‘de heart of de Souf,’ generally. As the steamer came near, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, ‘Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!’” Smalls had succeeded in the unthinkable—he had delivered his commandeered ship to the Union and delivered himself and sixteen other enslaved passengers to freedom.

The Charleston Courier reported the embarrassing news the following day: “Our community was intensely agitated Tuesday morning by the intelligence that the steamer Planter, for the last twelve months or more employed both in State and Confederate service, had been taken possession of by her colored crew, steamed up, and boldly run out to the blockaders . . . Between three and four o’clock, Tuesday morning, the steamer left Southern Wharf, having, it is supposed, on board five negroes, namely three engineers, one pilot, and a deckhand. Upon leaving the wharf the usual wharf signal was given by those on board, and the usual private signals given when passing Fort Sumter. The officer of the watch at the latter post was called, as usual, but observing the signal and supposing all right, allowed her to proceed. She ran immediately out to the blockading vessels. The Planter had on board four large guns destined for one of our new fortifications.”

Poetically, when the war ended in April 1865, Smalls was on board the Planter in a ceremony in Charleston Harbor.

The Planter was transferred to Port Royal, a Union stronghold near Beaufort. Officer Francis DuPont wrote to the Navy Secretary in Washington, D.C., of Smalls’s heroics. “Robert, the intelligent slave and pilot of the boat, who performed this bold feat so skillfully . . . is superior to any who have come into our lines—intelligent as many of them have been.” Smalls served in the Union navy and was given command of the Planter as her captain. His biographer, Edward Miller, explains, “As he was a knowledgeable pilot, his skills were in demand. On December 1, 1863, he was piloting the Planter near Secessionville when severe enemy fire caused the white captain to abandon his post. Smalls brought the vessel out of danger and was awarded with an army contract as captain of the Planter. He was the first black man to command a ship in U.S. service and remained captain of the Planter until it was sold in 1866. By his own count, Smalls was involved in seventeen military engagements during the war.” Gates notes, “Poetically, when the war ended in April 1865, Smalls was on board the Planter in a ceremony in Charleston Harbor.”

Reconstruction and a New Life

For his heroic delivery of the Planter, Robert Smalls and his family gained their freedom and fifteen hundred dollars, a small fortune at that time. The Smalls used the money to purchase his former enslaver’s Prince Street house in Beaufort as their new family home. Smalls entered the new political world emerging post emancipation, as the formerly enslaved found their footings as freed people, with new rights and the chance to vote and hold office. Old guard white South Carolinians and former Confederates were none too willing to share the stage with African Americans, so the federal government occupied much of the South in a complicated era known as Reconstruction, in which the nation was to transition to a place of equal rights for all.

Robert Smalls proudly served in the Republican party, vying for control against the Democrats (who in the nineteenth century were racially conservative and “lost cause” sympathizers). He worked alongside “carpetbaggers,” who migrated from the northern states to promote the rights of Black South Carolinians. In 1868 Smalls was part of the delegation from Beaufort that traveled to Charleston to draft a new state constitution, which offered a wealth of promising laws of equity for the future. Smalls added the proposal that “all children between the ages of seven and fourteen must attend public schools at least six months out of the year,” creating universal education for children, black and white, for the first time in the state.

Smalls served on the SC Senate, State House of Representatives, the US House of Representatives, and was a major general in the Beaufort militia in the 1870s. Permanent political change was an uphill battle in the state, but community leaders like Smalls never gave up the fight, even as Reconstruction ended and the Jim Crow laws became a reality in much of the South. In 1876 the Democrats seized control of state politics, marginalizing and disenfranchising Black citizens across the state. Fortunately, Beaufortonians had Smalls and fellow African American legislator Thomas Ezekiel Miller to push back against the prewar status quo. Smalls was known as an effective speaker and managed to hold office even after the resurgence of Democrat control of the state, at least briefly. He was one of six Black delegates at the 1895 South Carolina Constitutional Convention, where he tried but failed to prevent Black disenfranchisement. In his later years, he served as the Collector of Customs for Beaufort.

Legacies

Robert Smalls had three children with Hannah, and following her death, he married Annie Wigg and had one more child. His descendants still live in South Carolina today. Smalls’s great-great-grandson Michael Boulware Moore spoke of his ancestor’s bravery in a 2019 interview: “They knew that if they got caught, that they would be not just killed, but probably tortured in a particularly egregious and public manner . . . It really blew people’s minds because it just was beyond what people thought an enslaved person could do. There’s so many twists and turns in the story.” Smalls fought for the more than four million compatriots who were freed after the war to have equal rights and the ability to vote unmolested in the South, which roughly fifty-five years after his death became a reality thanks to trailblazing Civil Rights leaders of the 1960s who followed in Smalls’s and other freedmen’s footsteps.

The house at 511 Prince Street still stands, and in 2017 a Reconstruction Era National Monument was unveiled in Beaufort, with a bust of Smalls mounted proudly next to it. In Charleston, millions of tourists walk or drive by a new state historical marker at the foot of The Battery that is emblazoned with the story of Smalls’s daring Planter expedition. There is no better story of agency and success against all odds, toward equality. — C.B.

Journey to Freedom

STORY by Christina Rae Butler

IMAGES courtesy of NAVAL HISTORY AND HERITAGE COMMAND and NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY