History Comes Alive

Written by Stephanie Hunt

Photography by Sahar Coston-Hardy/Esto

Charleston’s International African American Museum is a long-awaited athenaeum on one of the most historically significant sites of the African American experience. A group of Kiawah residents and IAAM donors tour the museum with Chief Learning and Engagement Officer Malika Pryor.

On an unusually foggy morning in late fall, a group from Kiawah gathers at the edge of Charleston Harbor. The blue-gray water is glassy calm, and all but the very tip of the Ravenel Bridge is curtained by misty clouds. This veiled morning, with a hint of sunshine beginning to sparkle through, is eerily apropos—as if things both right in front of us yet also long obscured are suddenly brought forth anew. This is exactly what Charleston’s still-new International African American Museum (IAAM), which we are here to tour, does for our community and the broader world: It illuminates and honors the untold stories of the African American experience. Here at the water’s edge, with Fort Sumter and the Atlantic Ocean in the distance and the resplendent former homes of plantation owners just a seagull’s soar down the waterfront, the fog is lifting.

“We are standing on a portion of what was once Gadsden’s Wharf, the largest wharf and the most active during the transatlantic slave trade here in the port of Charleston, which was unquestionably the most prolific slave port in the United States,” explains Malika Pryor, chief learning and engagement officer for the new museum, which opened to the public in June 2023. She points to a brick outline on the East Garden lawn, near a towering grove of West African palms and in front of parallel black marble walls inscribed with Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise.” During archaeological digs as part of pre-construction site prep, the team discovered footings of former storehouses. “The brick represents the footprint of one of these warehouses where captive Africans were held until the laws of supply and demand moved the prices up, ensuring top dollar at auction,” she explains. “In the winter of 1807, records show that some seven hundred of those captive Africans died when temperatures dropped to freezing.”

Pryor shares such harrowing accounts without editorializing. She, like the museum itself, lets the facts speak for themselves, with a low-octave fortitude that carries its own power. Indeed, the IAAM is a testimony to the humbling hallowedness of presence. From the “floating” modular building’s non-rhetorical architecture, designed by the late Henry Cobb of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, to the ground-level African Ancestors Memorial Garden designed by Walter Hood of Hood Design Studio, every element is meant to be “interpretative and non-literal, creating space for us to be in conversation and in reflection. To remember our ancestors in a quiet and honored space,” says Pryor. Even for those not of African heritage, the story of the IAAM, she adds, is “a fundamental American story and an incredibly significant international story, and we believe those who crossed this wharf’s edge are thus part of everyone’s legacy and story.”

She leads us to that wharf’s edge, or rather, the steel band that demarcates where Gadsden’s Wharf once stood, inscribed with a litany of place names where captive Africans embarked from Africa and then their many points of arrival in the Americas. Perhaps the most evocative and artful part of the museum’s lower level is the “Tidal Tribute,” a ground-level horizontal fountain that rhythmically fills and empties, mimicking the ebb and flow of the tides, tying the museum to the Atlantic Ocean. The tabby basin is etched with abstract reliefs inspired by the Brookes Diagram, a sketch illustrating how to maximize the loading of human cargo in a slave ship’s hold. When Walter Hood first saw the diagram while on a research trip to Sullivan’s Island, he thought it evoked the graphic patterns of African textiles, and knew he’d found his inspiration. “When the fountain is full, the bodies almost appear as if on the bottom of the ocean. This acknowledges and honors the thousands who lost their lives during the Middle Passage,” Pryor says.

Hood’s garden-level design is infused with symbol and story at every turn, from benches surrounded with art installations, calling to mind slave badges, to a serpentine brick wall winding through wispy stands of sweetgrass, to a stele garden of abstract monoliths meant to honor African American heroes and ancestors, intentionally undesignated so viewers can choose and personalize their own steles.

Upstairs in the museum proper, however, specific African and African American heroes and notable figures, from early West and West Central African empires to colonial days in the Carolinas to the present day, get their due. Upon entering, an immersive multimedia corridor evoking the intellectual, spiritual, and cultural elements of the transatlantic experience sweeps you into the museum. From there, our group dissipates, peeling off in different directions—some towards the replica of a Praise House, others through the Atlantic Worlds and Gullah Geechee galleries, and others pausing to take in the chronological sections of the American Journeys gallery—all presenting a rich and nearly overwhelming bounty of history and information. Some move toward the West Wing, where a center gallery hosts special exhibitions—currently featuring a postmodern surrealist installation by Charleston-based artist Fletcher Williams.

The museum’s layout invites this to-and-fro wandering, which feels a bit like the African diaspora itself. Indeed, the free flow is almost necessary, as some exhibits, particularly the African Roots and African Routes section overlooking the harbor, are so riveting and heart-wrenching that it helps to step away for a bit to absorb it all. “Maybe you can see now why it took almost twenty years to bring [the IAAM] to completion,” Pryor says of the process that began in 2000 with then-Mayor Joe Riley’s vision for a world-class museum, to official groundbreaking in 2019, and finally the grand opening of the $96 million museum in June 2023. Our group nods, concurring that one visit is far from enough to take it all in. Which, our host suggests, is also intentional. “It’s not our goal to tell the whole story, but we are trying to represent a holistic story, so you walk away with a sense of continuity, with an experience that feels whole even though it could never be quite complete,” she adds. “It’s our hope that visitors are compelled to come back, to look further, to go deeper.”

“This is a dream come true,” says Kiawah resident and early IAAM supporter Brenda Lauderback. Reflecting on his visit, Lauderback’s Island neighbor Mark Permar, himself an architect and planner, shares the sentiment. “It’s an amazing building within the landscape that is more a story than a structure. The true test of architecture and landscape architecture is that it not only provides a platform for people to experience and deliver the intended use, but it gets better over time,” Permar says. “This place will live well, and people’s lives will be better because of it.”

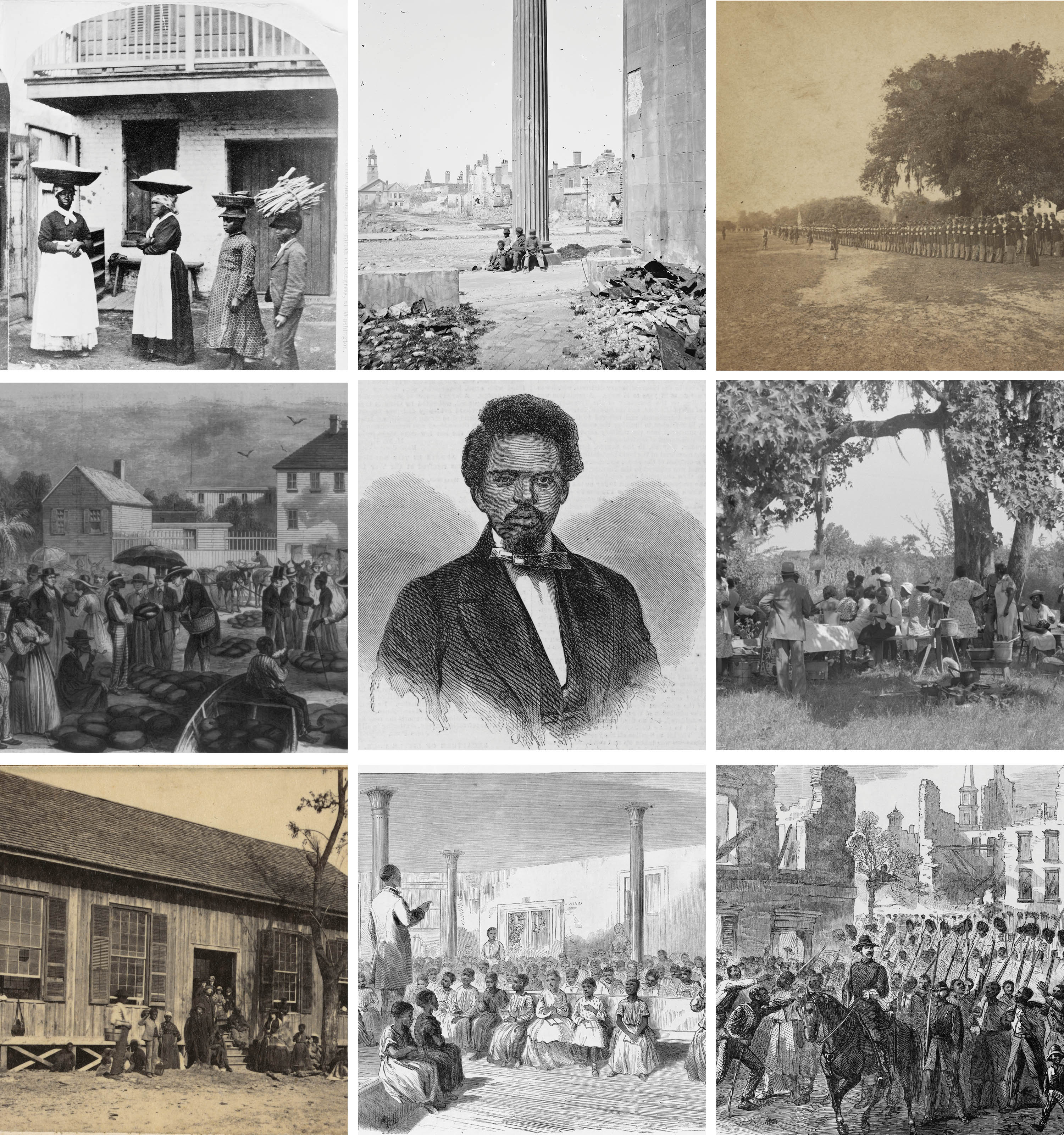

Charleston, South Carolina, has a profound historical significance in the narrative of African American heritage. Reverberating with echoes of both resilience and struggle, Charleston was a focal point of the transatlantic slave trade and holds a pivotal place in African American history. The city’s roots intertwine deeply with the African American experience, from Gadsden’s Wharf, where thousands of enslaved Africans first stepped foot on American soil to the rich cultural tapestry woven through Gullah Geechee traditions that persist in the Lowcountry. These images are part of the permanent exhibition of the museum an illustrates a Charleston history through time.

Credited left to right: African Americans working, Charleston, South Carolina || View of ruined buildings through porch of the Circular Church, Charleston, South Carolina, 1865 || First South Carolina Volunteers Hear the Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation near Beaufort, South Carolina, January 1, 1863 || Watermelon Market at Charleston, South Carolina, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1866 || Robert Smalls, captain of the gun-boat “Planter” || Watching a game at Fourth of July celebration, St. Helena Island, South Carolina, 1939 || Freedmen’s school, image by Samuel A. Cooley, Edisto Island, South Carolina, ca. 1862-1865 || Zion School for Colored Children, Charleston, South Carolina, by Alfred R. Waud, 1868 || “Marching on!”—The Fifty-fifth Massachusetts Colored Regiment singing John Brown’s March in the streets of Charleston, February 21, 1865