From Bonny to Blackbeard: South Carolina’s Golden Age of Piracy

Written by Christina R. Butler

The years 1670 to 1720 marked South Carolina’s Golden Age of Piracy. The coastline teemed with danger as pirates attacked foreign and friendly ships alike. Not to be confused with privateering, the legal practice where a private ship takes prizes on behalf of one’s own country, pirates robbed at sea indiscriminately. A wealthy fledgling colony with an important port, Charleston became a target for infamous pirates like Stede Bonnet and Blackbeard. Pirates were tacitly accepted in these early days because they brought goods for trade and wealth to spend.

George Raynor: Kiawah’s Pirate

George Raynor sailed in the early days of the colony when there was limited British Royal Navy presence. Raynor and his ship Loyal Jamaica arrived in the Charleston harbor in 1692 with a crew of forty men and “large quantities of silver and gold. By means of their wealth they found immediate favor and officials were so far swayed by considerations of which history does not speak, that they were permitted to remain in the province unmolested.” Grand Council records from April 1692 bear Raynor’s statement that his ship was a lawful prize taken in the war against France.

Raynor was a shrewd player and ended his career on a high note rather than capture and trial. He settled on Kiawah Island, at the time still a wilderness inhabited by the native Kiawah Indians. He allegedly kept two small patrol ships at Old Dock Creek on the backside of the island. By 1700 he had settled into polite society. Raynor was granted 2,700 acres on Kiawah (virtually the whole island), three town lots in Charleston, and over a thousand acres on the west side of the Stono River. He sold half of Kiawah shortly after receiving his land grant, and the other half passed to his daughter Mary Raynor Moore (who had married the governor’s son). Legends persist that part of Raynor’s treasure is still buried on Kiawah awaiting rediscovery.

Under False Colors: Lady Pirates

When the English were at war with the French and Spanish, their privateers pursued foreign ships on their way to and from the colonies along the South Carolina coast. During times of peace, however, many privateers turned to full-fledged piracy, leading to a resurgence of activity from 1716 to 1720. Pirates based in the Caribbean began creeping further north to the waters off Carolina in hopes of stealing valuable cargo from passing merchant ships. Stede Bonnet, Charles Vane, Christopher Moody, Anne Bonny, Richard Worley, and even the infamous Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, preyed upon the coastline.

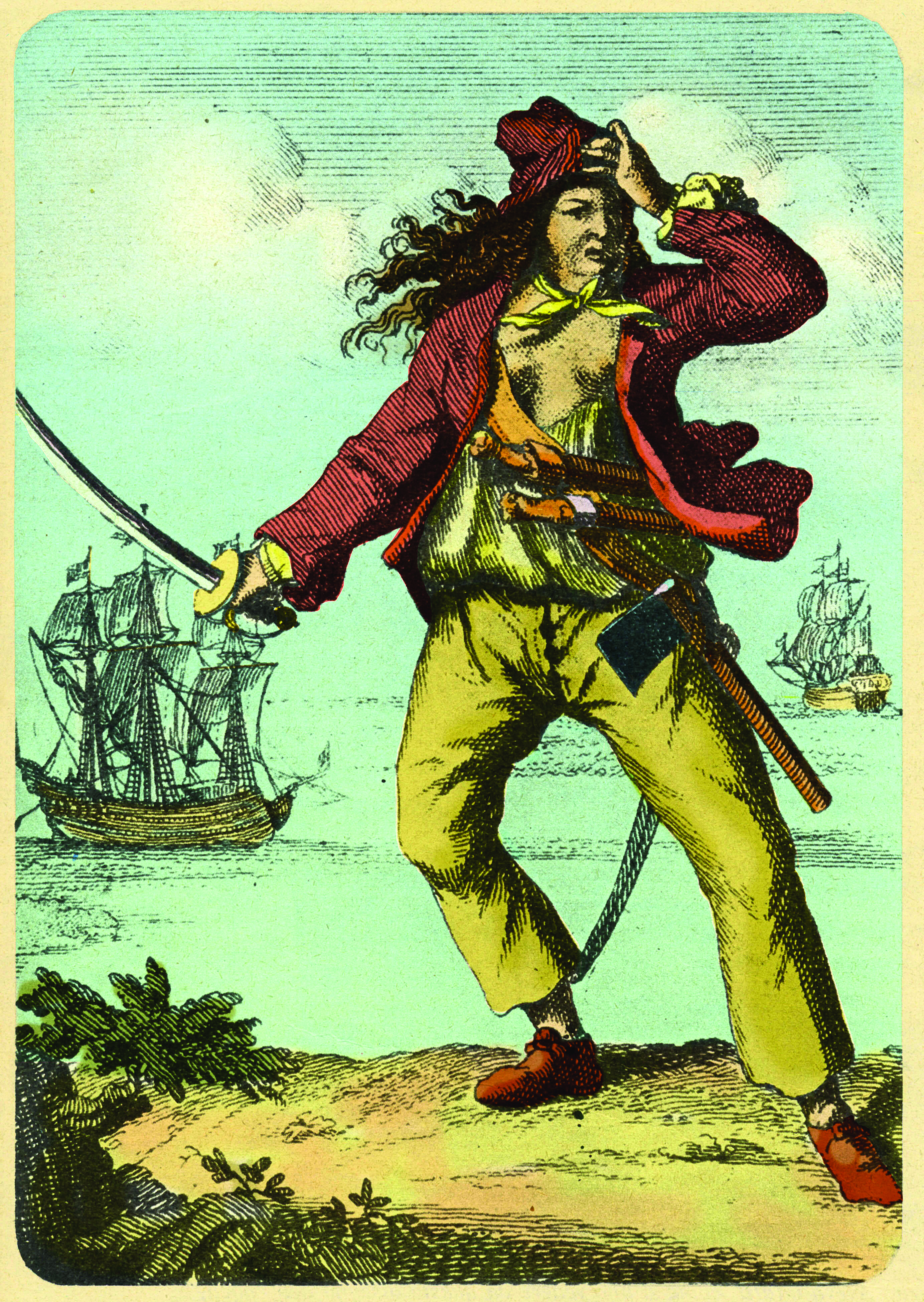

Lady pirates were uncommon, but the Golden Age of Piracy saw two: Mary Read and Anne Bonny. Bonny was born in Cork, Ireland, the illegitimate daughter of a maid and a married attorney. The attorney decided to raise his young daughter after the maid was imprisoned for theft, but “so as to disguise the matter from the town as well as his wife, he had put it in to breeches, as a boy, pretending it was a relation’s child he was to breed up to be his clerk.” Eventually young Bonny and her father headed to Carolina to start a new life, where he continued practicing law and Bonny kept house. Eyewitnesses said that Bonny “was of a fierce and courageous temper.” Bonny’s father hoped to marry her to a gentleman, but she met infamous pirate “Calico Jack” Rackham “and consented to elope with him and go out to sea in men’s clothes.”

Mary Read was born in England and allegedly disguised as a boy so her mother could pass her off as a deceased son to collect an inheritance. Legend states that Read later dressed in drag to join the military. When her ship was taken by Rackham, she willingly joined his crew. She met Rackham’s lover, lady pirate Anne Bonny, who “took a particular liking to her, took her for a handsome fellow.” They confided in one another and soon discovered they were both women. When Rackham threatened to cut Read’s throat out of jealousy, they let him in on their secret. Eventually the crew was captured and tried for piracy in Jamaica in 1720. Rackham and many of the crew were executed, but Read and Bonney were spared because they claimed to be pregnant. Read died from a fever in prison, and Bonney’s story ends in mystery, as no one knew what became of her after she left prison, only that she was not executed. Perhaps she returned to Charlestown.

Bonnet and Blackbeard

Meanwhile in Carolina, the infamous Stede Bonnet was menacing the coast. Born into wealth on the island of Barbados in 1688, Bonnet was a member of the planter elite and purchased a ship to begin his career in piracy. His contemporaries wrote, “The major was a gentleman of good reputation, was master of a plentiful fortune, and had the advantage of a liberal education. He had the last temptation of any man to follow such a course of life, from the condition of his circumstances. It was surprising to everyone to hear of the major’s enterprize . . . of going a pyrating . . . proceeded from a disorder in his mind, and which is said to have been occasioned by some discomforts he found in a married state.” Bonnet abandoned his wife and three young children for a life on the seas aboard the Revenge.

During his short career, Bonnet sailed to the Chesapeake, New York, the West Indies, Glasgow, the Caribbean, and to New Providence Island, Bahamas. He fell “into company with another pyrate, one Edward Teach, who for his remarkable black ugly beard, was more common called Blackbeard. This fellow was a good sailor, but a most cruel hardened villain, bold and daring to the last degree, and would not stick at the perpetrating the most abominable wickedness imaginable.” Born in Bristol, Blackbeard was an experienced seaman who worked his way up from deckhand to captain.

In September 1717 King George I issued a proclamation of amnesty to pirates who took an oath of good behavior. Bonnet accepted amnesty and resumed command of the Revenge in legal pursuit of Spanish ships along the American coast as a privateer. A life of crime on the high seas was too tempting, however, and Bonnet soon began indiscriminately attacking English and foreign ships alike. He terrorized the coast between Virginia and Carolina, taking thirteen prizes in just two months. Bonnet and Blackbeard managed to successfully blockade Charleston harbor for six days in May 1718, demanding medicine and supplies. Bonnet then went north to Delaware Bay and captured two sloops, the Francis and the Fortune, in July.

Bonnet’s luck ran out when he was captured in the fall of 1718 by Colonel William Rhett, who set out with two armed sloops, the Henry and the Sea Nymph, in search of the pirate ships terrorizing the coast. Historian Lindley Butler explains, “Rhett entered the Cape Fear River at dusk on September 26. The next morning a fierce six-hour battle was fought with cannons and small arms, ending with the surrender of Bonnet and his remaining men. Rhett returned to Charleston with thirty-six prisoners, ‘to the great Joy of the whole Province of Carolina.’” Bonnet managed to escape from Charlestown (legend has it he was disguised in women’s garb), before being caught again on Sullivan’s Island. Meanwhile, Blackbeard met his demise in 1718 in a fierce battle with Lieutenant Robert Maynard off Ocracoke Island in North Carolina. He was shot five times, and Maynard allegedly suspended Blackbeard’s severed head from the bowsprit of his boat.

The Pirate Trials

The pirate trials of 1718 were the spectacle of the decade, full of details of swashbuckling and descriptions of the infamous captains. Ultimately, Judge Nicholas Trott condemned forty-nine men to be hanged for their crimes on the high seas, in a series of thirteen trials. Twenty-nine of Bonnet’s crew, which included men from Jamaica, Aberdeen, Kent, Bristol, Antigua, Dublin, Holland, Gurnsey, London, and Glasgow (with aliases like “Timberhead” and “Rattle”), and William Smith, Jonathan Clarke, and Samuel Booth of Charleston were executed at White Point Gardens on November 8, followed by Bonnet himself at the same location in early December.

As English Admiralty law dictated, the men were hanged on the water’s edge between high and low tide. Historian Nic Butler explains, “Both Admiralty Law and Common Law claim jurisdiction over what is sometimes called the ‘intertidal zone,’ that is, the mudflats and beaches that are dry at low tide but underwater at high tide. This space is divisum imperium, or divided empire—a place where the legal jurisdiction alternates with the daily cycles of the tides. Capital offenses that were committed and tried at sea were punished by executions at sea. Capital offenses that were committed at sea but tried on land, however, were punished by executions within this intertidal zone.”

Legacies

Fear of pirates persisted throughout the eighteenth century, and occasionally Charlestown received reports of treachery off the coast, but Carolina’s Golden Age of Piracy essentially came to an end after the 1718 executions and with more protection from the British Royal Navy in the 1720s. Legends continued to circulate for decades, of hidden pirate treasures waiting to be uncovered along the Lowcountry coast. Still today, tourists and locals alike love a swashbuckling story of prizes and battles from the Golden Age of Piracy more than three hundred years ago.