A Prehistoric Paradise

Story by Dr. Mary Socci

Mastodons, giant ground sloths, and saber-toothed cats probably don’t spring to mind when you think of Kiawah Island wildlife. But at the peak of the last Ice Age, 21,000 years ago, these animals called South Carolina home. And that home would have been unrecognizable to its modern inhabitants.

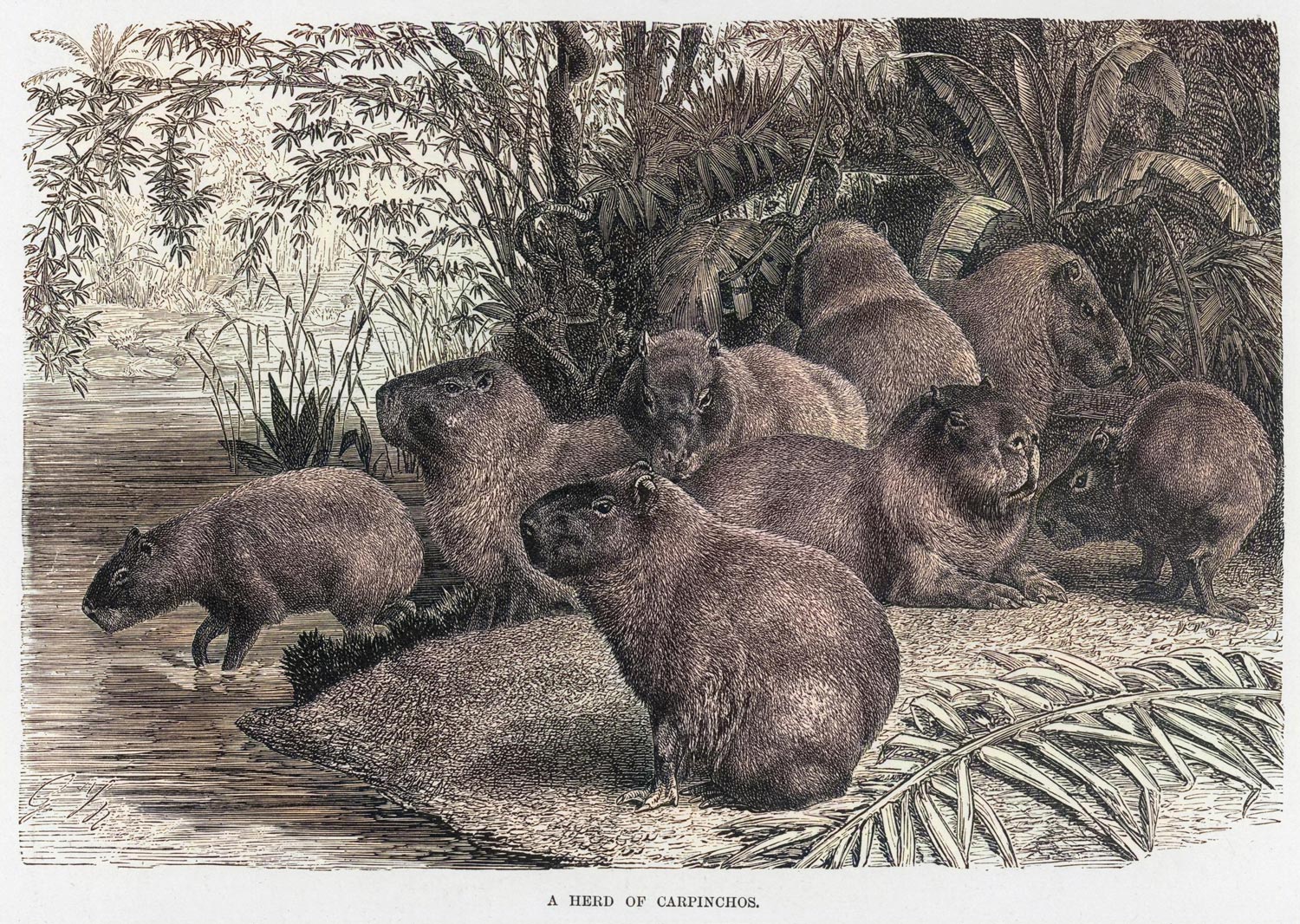

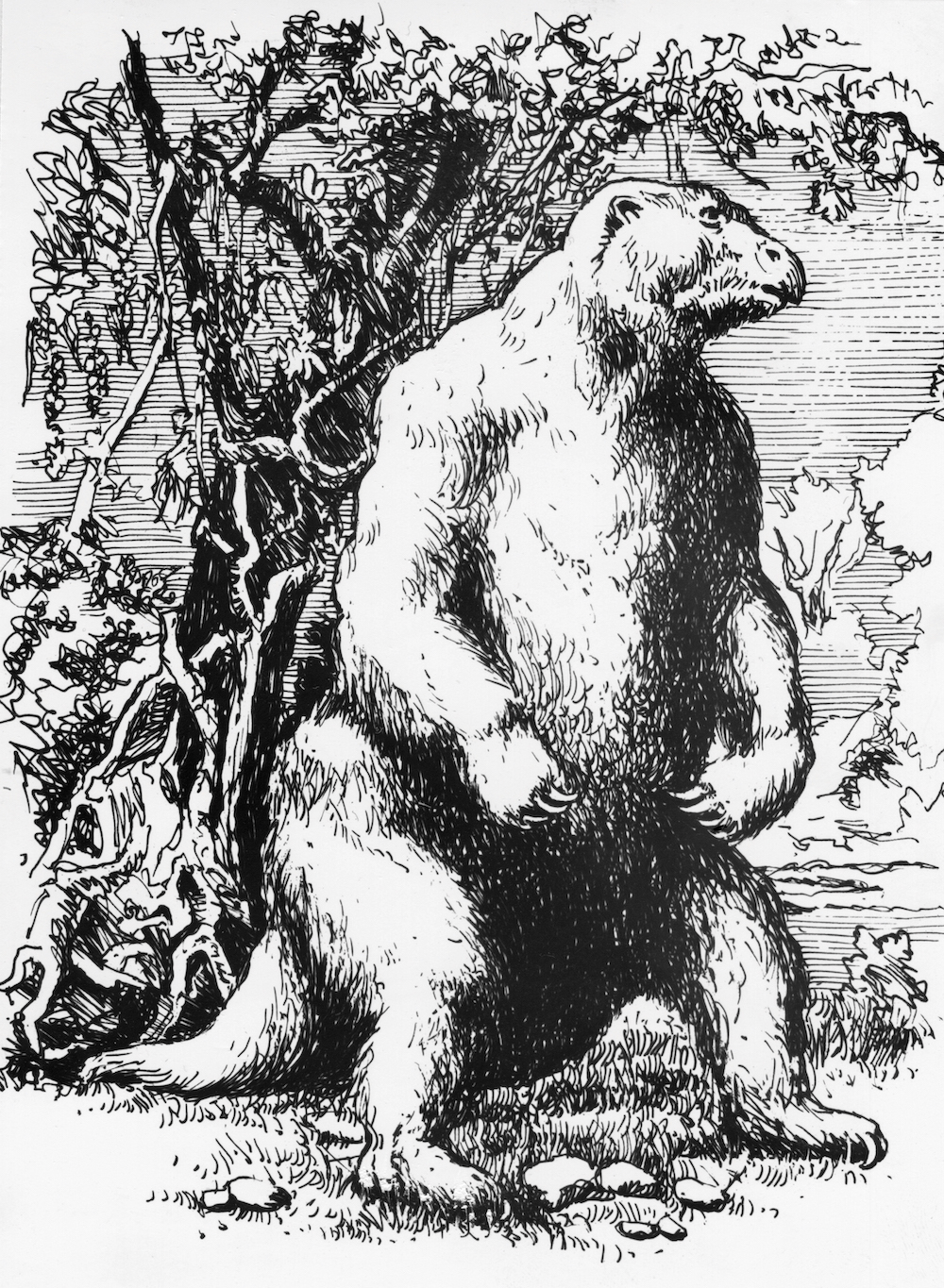

The Giant Ground Sloth, or Megalonyx, was around ten feet tall and weighed roughly 2,200 pounds. capybaras, depicted on the previous spread, once roamed the Southeast of North America.

On Kiawah Island, the tidal estuaries and maritime forest that surround us were thousands of years in the future. In fact, because so much water was frozen into more northern glaciers and snow, the sea level was much lower and a vast stretch of the continental shelf of North America was exposed. The marshes and waters of the Atlantic Ocean lay one hundred miles to the east of what are now our sandy beaches. Kiawah was not an island, just an inland section of the mainland.

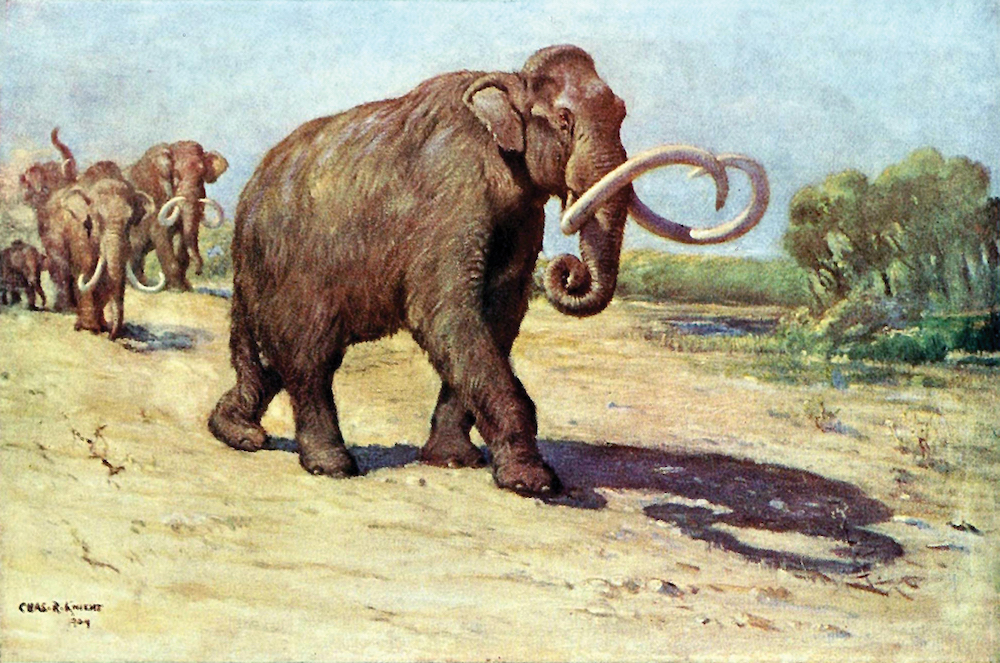

Evidence of Kiawah’s Ice Age ecosystem can be found in the Stono River and other nearby rivers and estuaries. Currents and tidal action have exposed fossils of teeth and bones from the prehistoric beasts that once roamed the Lowcountry. These fossils are consistent with what paleontologists have found elsewhere in the Southeast, and they reveal that South Carolina had a warm subtropical climate, despite the global cooling during the last Ice Age (150,000 to 11,000 years ago). For example, the mammoths that roamed what is now a sea island weren’t the woolly mammoths that wandered the tundra near the edge of the ice sheets. Instead, this was home to the Columbian mammoth, which stood about thirteen feet tall, two feet taller than its northern cousin. (Woolly mammoths were about the size of African elephants, nine to eleven feet tall). And Columbian mammoths weren’t woolly. They didn’t need thick fur because if the temperature ever dipped below freezing, it didn’t stay that cold for very long. Animals such as capybaras and giant tortoises, animals that no longer live in South Carolina but continue to thrive in the tropics, flourished in the mild climate of the Ice Age in the Lowcountry.

Despite the global cooling during the last Ice Age (150,000 to 11,000 years ago), South Carolina had a mild subtropical climate.

The fossils recovered from the rivers provide more than just a list of the animals that once lived here and clues about the temperatures, they also provide other details of the prehistoric environment. Mammoths, bison, and wild horses are grazing animals whose diets consist of a high percentage of grasses. The large number of fossils of these grazers (and fossil pollens from other locations) indicates that vast grasslands or savannas covered much of South Carolina’s ancient coastal plain. On the other hand, mastodons primarily ate the seeds, leaves, and even small branches of shrubs and trees, as well as grasses and sedges. The presence of mastodon fossils corroborates botanical studies that suggest patches of forests and copses along wetlands broke up the expanse of grasslands.

Although similar in appearance, mastodons and mammoths are only distant relatives. (Mammoths are more closely related to modern elephants than they are to mastodons.) Mastodons were smaller, about the same size as an elephant, and their tusks were less curved. Mastodons grazed on leaves, twigs, and the seeds of shrubs and trees while mammoths grazed on grasses. This difference in diet meant that mammoths and mastodons occupied different niches in the same ecosystem.

Although fierce predators, such as saber-toothed cats, jaguars, American lions, and dire wolves, stalked the large herbivores of the Ice Age, it may have been the combination of changing climate and human hunting that caused the extinction of these animals. In Alaska, the lower sea level during the Ice Age exposed an isthmus of land—the Bering Land Bridge—that connected western Alaska to eastern Russia. Hunter-gatherers who had lived in Asia for millennia took advantage of the new connection and became the first people (called Paleo-Indians by archaeologists) to inhabit the Americas, around 23,000 years ago. Likely, the earliest arrivals moved south along the coast, fishing and hunting seals. Eventually, as groups reached the southern edge of the great ice sheets, some moved inland, spreading into North America and down into South America. Approximately 12,000 years ago, Paleo-Indians were hunting the savannas of the Lowcountry.

By the time the Paleo-Indians arrived in the area of what would become Kiawah Island, the Ice Age was ending. Warmer temperatures were melting the vast ice sheets that covered the northern and southern ends of the earth, and the sea level was rising. Over the following millennia, the sea continued to rise until about 6,000 years ago. The coastline was much like that of today: the Stono River flowed with the tides; live oaks, longleaf pines, and palmettos grew up in what had once been grasslands; and the sea surrounded Kiawah, creating the Island and the iconic sandy beaches we now enjoy.