Wild Islands

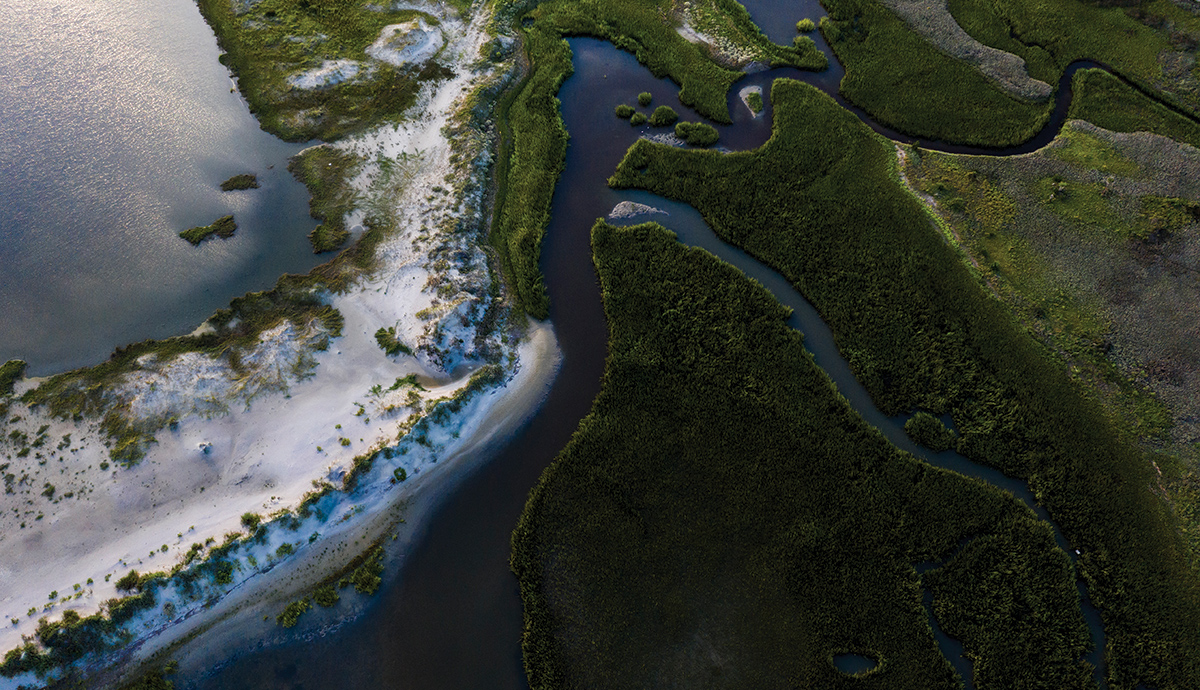

The barrier island system is made up of geological striations of sand, forest, and marsh.

The barrier islands of the Carolina Lowcountry are like no other ecosystem in the world. These unique land formations boast an outsized number of contrasting ecosystems and are home to countless rare and endangered species of both plants and animals.

Barrier islands exist in chains, separated from the mainland by a shallow sound or narrow tidal inlet. The formation of these islands is complicated and not completely understood. Most geomorphologists believe that at the end of the last ice age, as glaciers melted and receded, sea levels rose and flooded existing beach ridges, pushing sediment out and depositing it along shallow areas just off the new coastline. Additionally, freshwater, carrying sediment from distant mountains, continues to empty into the low-lying coastal plain, where it is met by opposing tidal forces pushing saltwater shoreward. Over time, waves and currents build up sediment while weather events periodically reshape barrier islands more drastically.

The barrier island system is made up of geological striations of sand, forest, and marsh. From ocean to inlet, the first layer is a wide, sun-bleached beach. Much of the beach is entirely covered with saltwater twice daily, and sand is deposited day after day by the Atlantic’s gentle waves.

Known more specifically as the intertidal zone, burrowing animals that live here—like mole crabs and clams—have adapted to daily exposure to saltwater and filter feed during high tides. A wide variety of shorebirds are on display, from sandpipers scavenging crustaceans to terns, and brown pelicans plunging into the water in pursuit of offshore fish.

Moving into the interior of the island, you make your way over a series of ever-changing dunes, formed by windblown sand. The dunes are stabilized by sea oats, bitter panicum, and other plants—their shoots slowing the wind and allowing sand to be deposited. This is crab country, particularly ghost crabs that live here within range of the salt spray, accompanied by the gulls that feed on them and other invertebrates.

Most geomorphologists believe that at the end of the last Ice Age, as glaciers melted and receded, sea levels rose and flooded existing beach ridges, pushing sediment out and depositing it along shallow areas just off the new coastline.

Protected by the dunes, the sun filters through a canopy of splash pine, sand live oak, and flowering magnolia.

You next enter the shade of maritime forest. Protected by the dunes, the sun filters through a canopy of slash pine, sand live oak, and flowering magnolia, as well as large shrubs and small herbaceous plants. The tracks of racoons, opossums, bobcats, and foxes cover the soft earth. A bright warbling echoes through the canopy, and you see the unmistakable blue head, red throat and chest, and green back of the brilliantly plumed male painted bunting.

Emerging from this dense copse, it takes a moment for your eyes to adjust. Looking west, the salt marsh glimmers in the sun, a kaleidoscope of green cordgrass, shimmering mudflats, and meandering creeks reflecting the brilliant blue of the sky. Settling into a waiting kayak, you shove off, paddling along the calm water of a tidal creek, navigating oyster bars as an ebb tide propels you out toward the River.

The salt marsh is one of the most productive ecosystems in the world, supporting an astonishing multitude of vegetation per acre and requiring a rare confluence of forces to exist. The low elevation allows the existence of vast estuaries, home to only one kind of grass but a rich diversity of wildlife. The magic ingredient—Sporobolus alterniflorus—is a perennial, deciduous grass that grows and dies off annually, forming the building blocks of life in the wetland ecosystem.

Just as your eyes adjust, so now do your other senses. First there is the distinct smell accompanying your journey through the marsh. Pluff mud—a viscous, dark-brown miasma of decomposing grasses. But though these tidal flats may not appear “clean,” they perform an important function of purifying runoff from mainland rivers and streams.

The audio component of your experience is no less unique. A gentle breeze sighs through the cordgrass, interrupted by the distinct kekk-ing calls of clapper rails, known colloquially as marsh hens. The distant but ubiquitous pop of snapping shrimp claws reaches you through the water. Paddling around a bend you startle a great blue heron. The massive, blue-gray bird omits an indignant Jurassic croak as it takes flight.

The salt marsh is one of the most productive ecosystems in the world, supporting an astonishing multitude of vegetation per acre and requiring a rare confluence of forces to exist.

These barrier islands are situated along the Atlantic Flyway – a major migratory route for birds traveling from as far off as Greenland and South America.

It’s almost as if this fickle marine environment is teasing the abundance of extraordinary life all around, without revealing too many secrets.

Where the beach and interior of the island are beautiful— the marsh astounds. The huge source of nutrients produced from the decomposing cordgrass supports an abundant diversity of species specially adapted to the region. From phytoplankton in the water to diamondback terrapins (the only turtle living in the saltmarsh, having developed glands to process the salt) to an abundance of birdlife.

Elegant snowy egrets, white with bright yellow feet, stalk the shoreline as you enter the main channel of the Kiawah River. You pass a shell rake hosting five willets and a ruddy turnstone. Bald eagles and ospreys wheel high above, and a belted kingfisher perched on a high snag lets out its wild rattling call before diving headlong into the water. These barrier islands are situated along the Atlantic Flyway—a major migratory route for birds traveling from as far off as Greenland and South America—and play an important role as a stopover between breeding and wintering grounds.

The breeze has picked up as you head upstream, sending a spray of water from the end of your paddle. Your destination, the Cassique boat dock, is in the distance. Just then you see them, a pod of dolphins. You pull your paddle out of the water as they approach, until they surround you on all sides. A mother and her calf surface ten yards away, rolling up out of the water, eyeing you calmly before submerging again. Magic.

The barrier island ecosystem is unforgettable. Her wild marshes and estuaries are a potpourri for the senses— an enchanting place that lodges deep down in the brain, immediately recognizable and remembered. She’s capricious, perhaps an acquired taste, but one that rewards the patient, appreciative observer through a slow revelation of her wondrous charisma and nuance.

Spoonbills, alligators, dolphins, redfish—who knows what you’ll encounter? Take the trip and see if it changes you. — J.C.

Wild Islands

STORY by JOEL CALDWELL

PHOTOGRAPHY by GORDON KEITER and MEL TOMS