Brinks and Boundaries

VOLUME: 32

Written by

Christina Rae Butler

Photographs by

The Library of Congress, The Gibbs Museum and The Carolina Art Association, The Charleston Register of Deeds

“The Framing of Early Charleston”

As you stroll South of Broad, it is hard to imagine the soft edges of marshland that once encircled the peninsula, the muddy tidal creeks where Water Street now lies, or the grazing land that surrounded the small pond that is now Colonial Lake.

A SKETCH OF THE OPERATIONS BEFORE CHARLESTOWN, THE CAPITAL OF SOUTH CAROLINA | 1780 | DesBARRES, JOSEPH F.W. | LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

We have early engineers and land speculators to thank for making Charleston what it is today—a landmass nearly twice its original size. Over the past three centuries, the shape of the Charleston peninsula has evolved dramatically. Residents and city planners used a variety of means and materials to create more buildable land and a harder border between the city and the ever-present tidal rivers that brought cooling breezes, erosion, and flooding potential in equal measure.

A VIEW NEAR CHARLESTON | CHARLES FRASER | COURTESY OF THE GIBBS MUSEUM AND THE CAROLINA ART ASSOCIATION

Early settlers and visitors to Charlestown built on the highest part of the peninsula first, on the banks of the Cooper River, wedged between two large tidal creeks: Daniel’s Creek (what became Market Street to the north) and Vanderhorst Creek (now Water Street to the south). And as tensions between the English colonists in Carolina and the Spanish in Florida ran high, the colonial government fortified the town and built a wall around the most settled area. Alexander Hewatt described the town in 1779:

“It is situated on a neck of land at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper rivers, which are large and navigable, and wash at least two-third parts of the town. The streets from east to west extend from river to river, and, running in a straight line, not only open a beautiful prospect, but also afford excellent opportunities, by means of subterranean drains, for removing all nuisances, and keeping the town clean and healthy.”

The walls and creeks that defined this early community are depicted on a map by Edward Crisp drawn in 1711. The map shows the marshland where White Point Garden and Harleston Village now lie.

McCRADY PLAT #490, LANDS BELONGING TO THOMAS ESQUIRE | COURTESY OF THE CHARLESTON COUNTY REGISTER OF DEEDS

Charlestown became a prominent port city, and the population grew, prompting residents to fill creeks, marshes, and rivers to create more land. They used street sweepings, mud, sand, ship ballast stones, rice chaff, sawdust, and even trash—whatever was readily available and cheap to acquire. Residents reclaimed and filled to create seawalls and embankments to protect the town from erosion. John Lambert, who visited in 1807, remarked, “The site of Charleston nearly resembles that of New York, being on a point of land . . . The town is built on a level sandy soil, which is elevated but a few feet above the height of spring tides. From its open exposure to the ocean, it is subject to storms and inundations, which affect the security of its harbor.”

By the American Revolution, the town had grown northwardly up the peninsula, and slowly west and south into the Ashley River marshes. The town limits were moved to Boundary Street (Calhoun Street) to meet development. A beautiful hand tinted plat from 1798 shows new lots laid out along the marshes at the west end of Calhoun Street, bounded on the east by a Negro Burial Ground (part of College of Charleston’s campus today), Daniel Cannon’s land nearer the Ashley River to the west, and Thomas Radcliffe’s land to the north.

AN EXACT PROSPECT OF CHARLESTOWN, THE METROPOLIS OF THE PROVINCE OF SOUTH CAROLINA | 1762 | LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Inconveniences of a Low Situation

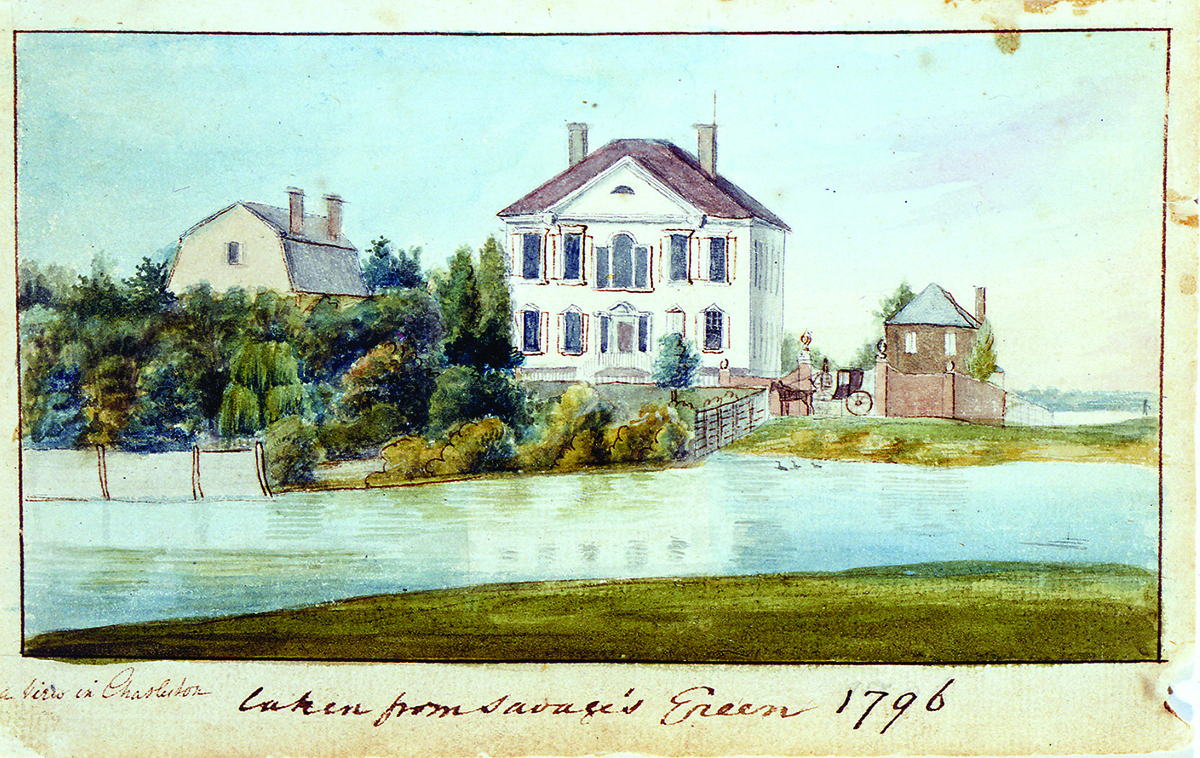

Some of the best descriptions and illustrations of early Charleston come from portrait painter and artist Charles Fraser, who was born in the city in 1782. His watercolors beautifully depict marsh-front houses landlocked by later reclamation, and riverbanks that are now under street beds. He also published his youthful memories of Charleston in his Reminiscences of 1854. He wrote of Harleston, a late eighteenth-century neighborhood on the Ashley River, west of the original town settlement, “That extensive portion of the city, so handsomely improved, was then unoccupied, and penetrated by creeks and marshes; and there was nothing to interrupt the view of the College [of Charleston] buildings from Cannon’s Bridge, where the boys used to bathe.” Cannon’s Bridge was a causeway near Calhoun Street, over the Ashley River creeks.

West of Magazine Street was nothing but marsh, and at the west end of Broad Street, the land beyond Savage’s Green (near Savage Street today), “was entirely vacant. That green was separated from the lots on Tradd Street, by a marsh which ran through the present site of Logan Street, nearly up to the corner of Friend [Legare] and Broad Streets.”

At the Market, Fraser remembered “the Governor’s bridge, a wide brick arch thrown across a creek, into which the tide flowed, from where the fish market now stands nearly up to Meeting Street, and covering the whole extent of our present market.” Water Street “was another creek, through which the tide ran some distance. I have often, when a boy, swum through a brick flood gate next to where Mr. D. Ravenel’s house now stands. The low ground, which yet remains in that neighborhood to be filled up, indicates its locality. This floodgate had, no doubt, been placed there to prevent the encroachments of the sea, and give safety to the fishing boats, which I remember seeing there in great numbers.”

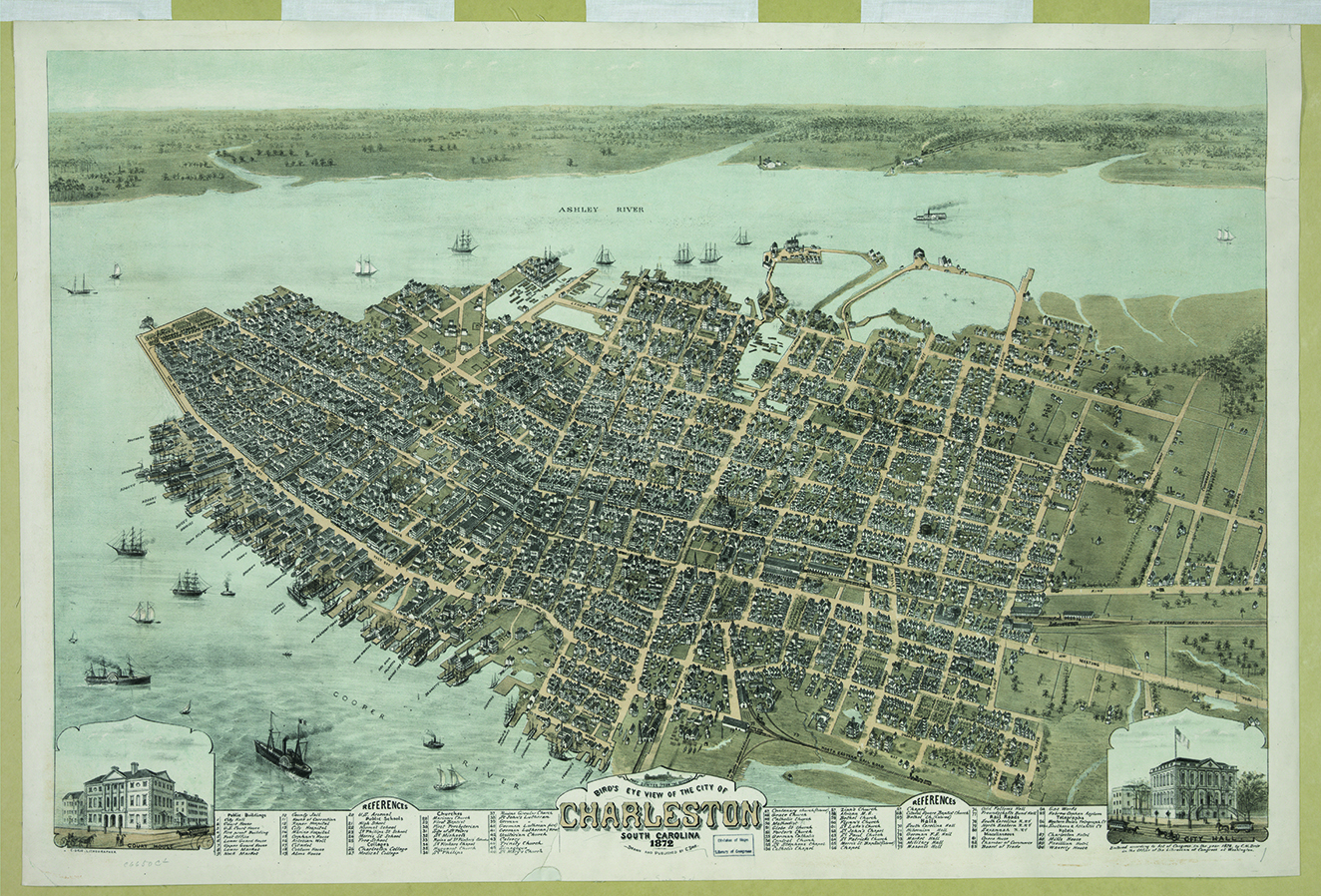

BIRD’S EYE VIEW OF THE CITY OF CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA, EXCERPT | 1872 | DRIE, C.N. | LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The flood gate and neighboring Fort Mechanic (a large fortification in place during the War of 1812, located where 17 and 19 East Battery are today) was gone by the antebellum era. The City constructed the high stone East Battery seawall, with its promenade and view of the harbor and Fort Sumter, out of the former Cooper River mudflats. The wall kept the waves and tides at bay and provided a popular scenic walk. A British visitor remarked, “The Battery is their Hyde Park, their Prater, and their Champs-Élysées and they are justly proud of it,” although he warned, “When you go out to enjoy a stroll, if the air is still, a beefsteak could frizzle on the crown of your hat.” At the southern end of the peninsula, White Point Garden was reclaimed from the Ashley River. Where pirates were hanged on a bleached oyster shell beach in 1718 and gun batteries were mounted during the Revolution, a fine park with benches, oak trees, and strolling paths now stood.

Not all waterfront properties were desirable, however. The marshes and mudflats were untraversable, low lying areas often flooded the streets, and swamps emanated noxious smells. People in the nineteenth-century believed that bad air vapors could make them ill and tried to avoid lowlands when possible. Tidal drains carrying runoff water laced with manure from the streets might also empty into waterfront areas that were industrial and shipping hubs. British author and sociologist Harriet Martineau wrote of her experience in Charleston in 1835 that “the soil is a fine sand, which, after rain, turns into a most deceptive mud; and there is very little pavement yet. They told me that a horse was drowned last winter in a mudhole in a principal street.”

Alongside the older part of the city to the south, ponds were created from marshes along the Ashley River to service rice mills like West Point, owned by the Bennett and Lucas families and accessed by long causeways. Lumber mills and windmills, like those painted by Fraser, lined the west side of Harleston Village. Colonial Lake fronted the Ashley River and other log ponds in 1900, and is itself a vestigial millpond-turned-reflecting lake, now hundreds of feet from the banks of the Ashley River after decades of filling and development.

In the late nineteenth century, residential development crept ever-northward. An 1864 map of the peninsula shows the marshfront neighborhoods north of Calhoun Street, White Point Garden (half the size it is today), and mill ponds along the west side of the city. New neighborhoods like Cool Blow, Hampton Park Terrace, and Wagener Terrace provided residential enclaves accessed by the new electric trolley system begun in 1897. Hampton Park and Terrace began at the turn of the nineteenth century as Washington Race Course, where gentlemen could catch breezes from the Ashley River and watch horses race. It served as a prisoner of war camp during the Civil War, then an exposition ground in 1901-1902, before becoming a park and residential area.

A VIEW IN CHARLESTON TAKEN FROM SAVAGE’S GREEN | 1796 | CHARLES FRASER | COURTESY OF THE GIBBS MUSEUM AND THE CAROLINA ART ASSOCIATION

The Parks and Murray Boulevard

Constructing Murray Boulevard, one of the more ambitious waterfront changes of the twentieth century, occurred in two phases in the 1910s. The timing couldn’t have been worse because World War One led to material rationing and labor shortages throughout the state, but after almost a decade, workers had created forty-seven new acres of lots and promenades alongside the Ashley River, linking the White Point Garden area with the earlier reclamations near Colonial Lake on the west side of the peninsula.

Charlestown’s original topography lies beneath the Charleston of today. The waterways that once cut across the peninsula remember their path, occasionally reasserting their presence in the summer’s tropical downpours. Current residents, however, are fortunate for their industrious forerunners’ efforts to create a thriving port city from the lowlands. Today you can stand on this land and take in the marsh and rivers from the pathways of White Point Garden and Waterfront Park. — C.B.