THE CIVIL WAR

VOLUME: 28

Written by

Christina Rae Butler

Photographs by

Provided

“Deemed the “hellhole of secession” by famed Union general William Tecumseh Sherman, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union.”

In December 1860, 169 state representatives met in Charleston to sign the Ordinance of Secession. Morale was high as three thousand citizens cheered the delegates. Then on April 12 of 1861 Charleston was witness to the first shots of the Civil War at Fort Sumter. Locals lined the Battery facing the harbor to cheer the Confederacy. Few Lowcountry residents could have guessed that the war would drag on for four more years, causing untold desolation to the city and plantations on the surrounding Sea Islands like Kiawah.

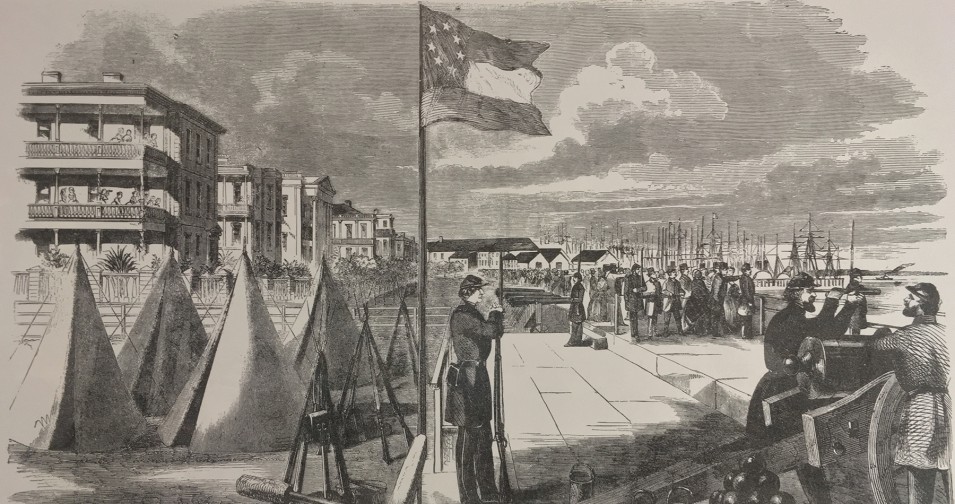

The Early Years

By early 1861, after several months of Union activity in the Harbor, Charlestonians knew it was a matter of time until the war would begin. Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard sent word to Union major Robert Anderson to surrender Fort Sumter, or his troops would start firing. Anderson refused, and at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, the Confederate batteries opened fire on the Fort. By nightfall 2,500 shots and shells had been fired as spectators cheered from the Battery. At 2:30 p.m. on April 13, Anderson surrendered. Fort Sumter was now in the hands of the Confederacy and would remain so until 1865. A female Charlestonian exclaimed, “Victory was ours, and the Stars and Bars . . . floated beside the Palmetto from the battered walls of Sumter.”

Almost immediately President Lincoln called for the enlistment of seventy-five thousand troops to fight the Confederate States. Union blockade ships began patrolling the coast off of Charleston and Savannah. On November 7 a Federal fleet launched an amphibious assault and quickly took Hilton Head, Port Royal, and Beaufort. South Carolinians were shocked that Beaufort had been taken, and many residents on the Sea Islands to the south of Charleston panicked and moved with their slaves to the interior of the state.

Charleston saw no fighting for the rest of 1861 but suffered tragedy on December 11, 1861, with the worst fire in its history. Though not a result of the Civil War, the fire caused $3.5 million in damages (an 1861 valuation) and destroyed more than five hundred buildings as it burned its way from the Cooper River westward across the city.

Fear of slave insurrection and paranoia was rampant in Charleston. Slaves continued to run across enemy lines in hopes of finding freedom and shelter with the Union troops. Bored Confederate soldiers roamed in drunk and disorderly bands around the city, vandalizing, firing their guns, and causing general mayhem. Resident William Grayson remarked, “No destruction of Lincoln’s men could be more complete and unsparing.”

But despite the catastrophic fire and heightened danger, morale was still high. Young women dined and danced with officers at seasonal balls. Local women contributed to the war effort through charitable groups and the Ladies Gunboat Society, which raised enough money to finance a ship called the Palmetto State. Lowcountry residents found purpose in the midst of the conflict. Life went on.

The War Escalates

Northern forces viewed Charleston as a hot spot and were determined to take it at all costs. In June 1862 six thousand troops launched an attack on five hundred Confederates, and fighting began locally in earnest. The first Union force was unsuccessful, and leaders prepared for another assault. Beauregard commanded his men to shore up the city’s defenses by strengthening the earthen batteries and adding more guns to the “circle of fire” protecting the harbor. Union forces tried the next naval attack in April of 1863, but their nine ironclads could not breach Sumter or the city.

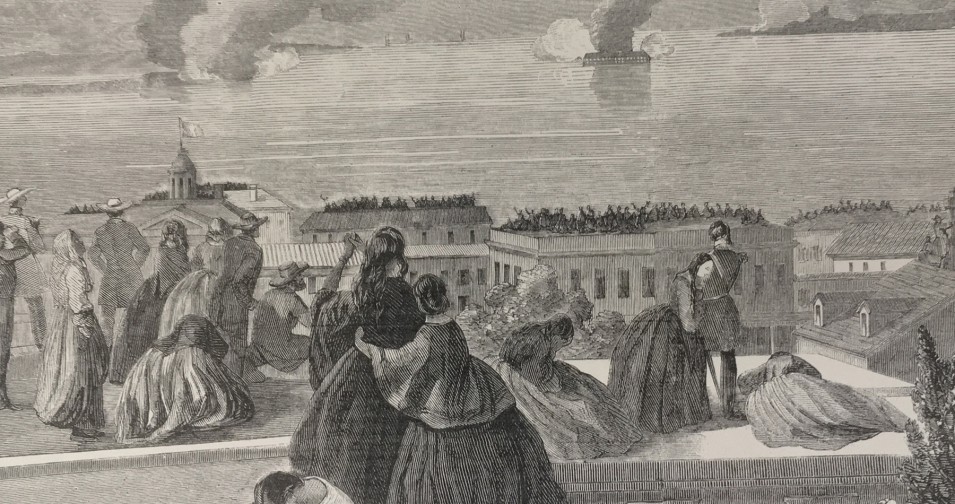

Skirmishes continued on James Island into 1863, and in July Union leader Quincy Gillmore stormed Battery Wagner on Morris Island with thousands of troops, including the famous black unit the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. As they invaded the islands around Charleston, other Union forces fired at Fort Sumter. A reporter in the city described the ensuing mayhem:

The good people of Charleston had been anxiously awaiting the Federal assault, which they knew to be imminent. Theirs was not an anxiety of fear . . . so thoroughly indifferent were the ladies of Charleston to any sense of danger, that an order issued by General [Beauregard] for all women and children to leave the city was in most cases disregarded. But suddenly the southern eastern parapet of Sumter is enveloped in smoke. Boom! Comes the report over the quiet waters of the bay…every house is pouring out its inmates, eager to witness the engagement. The bay, lately so calm and peaceful, is now like a seething cauldron…huge spiral columns of water leap into the air around the ironclads.

After several unsuccessful attempts to take Charleston by water, the Union launched a different tactic—shelling Charleston civilians from James and Morris Islands. Gillmore set twenty-two thousand men to work erecting gun batteries in the island marshes facing the Charleston peninsula and Fort Sumter. The batteries were five miles from the city, too distant for conventional ordnance to reach, so residents were at first unconcerned. However, recent weapon developments and rifling technology actually put the city in range, and on the night of August 22, 1863, the “Swamp Angel” gun opened fire on Charleston.

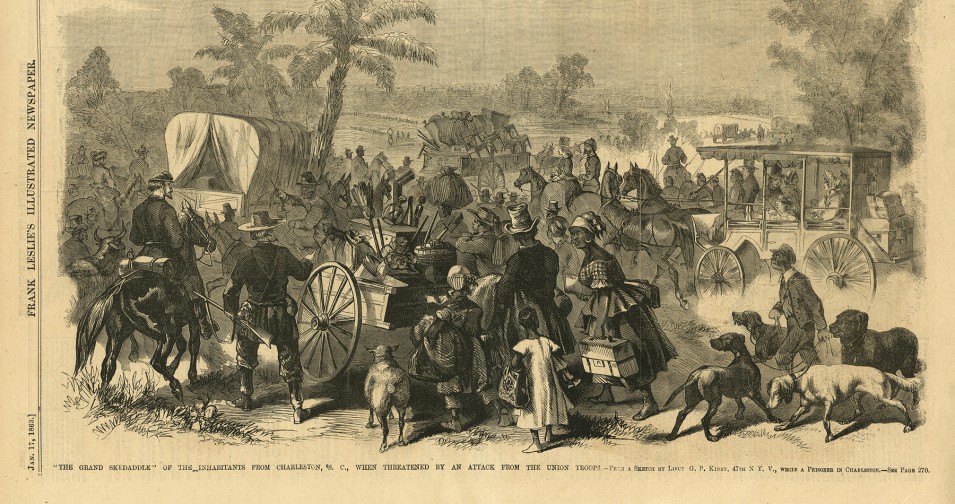

The first shell hit Hayne Street near the Market, narrowly missing the Charleston Hotel. A British visitor recalled, “At first I thought a meteor had fallen, but another awful rush and whir right over the hotel and another explosion beyond, settled any doubts that the city was being shelled.” Beauregard admonished Gillmore: “It would appear sir, that despairing of reducing our works, you now resort to the novel measure of turning your guns against old men, the women and children, and the hospitals of a sleeping city, an act of inexcusable barbarity.” Church steeples became targets for Union artillery, so many closed during the siege for the safety of their parishioners. Newspapers reported that many residents had made a “Grand Skedaddle,” leaving as quickly as they could pack their belongings.

Those who stayed became used to the daily explosions. Fitz Ross, a visiting journalist, wrote, “Nine out of ten shells fall harmless—the hope of the Yankees to set fire to the city or batter it down have hitherto proved disappointing.” The shelling continued with varying degrees of intensity for 587 consecutive days. In January 1864 the Charleston Mercury did report a frightening near miss: “One of the enemy’s large shells, after penetrating the roof of a dwelling, overturned a bed in which three young children were sleeping, throwing them rudely on the floor, but then strange to say, it passed without bursting, and buried itself in the foundation of the house.”

The worst bout of shelling occurred during a nine-day stretch in 1864, when over fifteen hundred shells rained down on the city. Volunteer fireman Charles Rogers wrote to his wife in June 1864 that “there was a fire downtown last week, and the Yanks dropped their shells in town like peas…I have experienced a remarkable change since my return. In fact it is a matter of much congratulation in the Starvation times. I don’t eat half as much now.”

The city established a free market and Subsistence Committee, but food was hard to come by, because the few farmers who still had produce were not willing to make the dangerous trek into shell-shocked Charleston. Mary Chesnut wrote, “Privateering has gone mad, and there is suffering, damage, and death on every side.”

Kiawah Island

Johns, Wadmalaw, and Kiawah Islands were far enough from the Peninsula that they saw less action, but they were not untouched. In 1862 the Confederate leaders called for residents to evacuate the islands, as Union forces continued patrolling the coast. At the Vanderhorst, Seabrook, and Wilson family plantations on Kiawah, a few trusted slaves were left behind to protect the properties.

On February 8, 1863, twenty-three hundred Union troops landed on Kiawah and marched through Haulover Cut to Johns Island. Thirty-one men were killed in a short skirmish with the Confederates. In September 1863 Gillmore gave orders for his troops to “reconnoiter Kiawah Island thoroughly” and to patrol the island to prevent Confederates from building batteries near the Union bases. Union troops built rifle pits, a boat landing, and two earthen forts. Kiawah was used as a campground and base for shipping materials to the nearby Union batteries, but the island was otherwise largely deserted.

Gillmore gave orders for his troops to “reconnoiter Kiawah Island thoroughly” and to patrol the island to prevent confederates from building batteries near the Union bases.

The End Draws Near

In 1864, as the attack on Charleston became more intense, the city’s services deteriorated. When General William J. Hardee took command of the southern coastal forces in October, he found many of the soldiers barefoot and poorly armed, trained, and fed. Meanwhile, General Sherman marched southward with sixty thousand trained Union soldiers.

Savannah was evacuated December 21, 1864. Hardee relocated sixteen thousand troops to Charleston, believing the city would be Sherman’s next target. Despite the Union general’s hatred of the “hellhole of secession,” as he neared Charleston and left burned plantations, looting, and destruction in his wake, he decided to bypass the city, which was a “mere desolated wreck . . . hardly worth the time it would take to starve it out.” Instead, he marched to Columbia and destroyed much of the state’s capital.

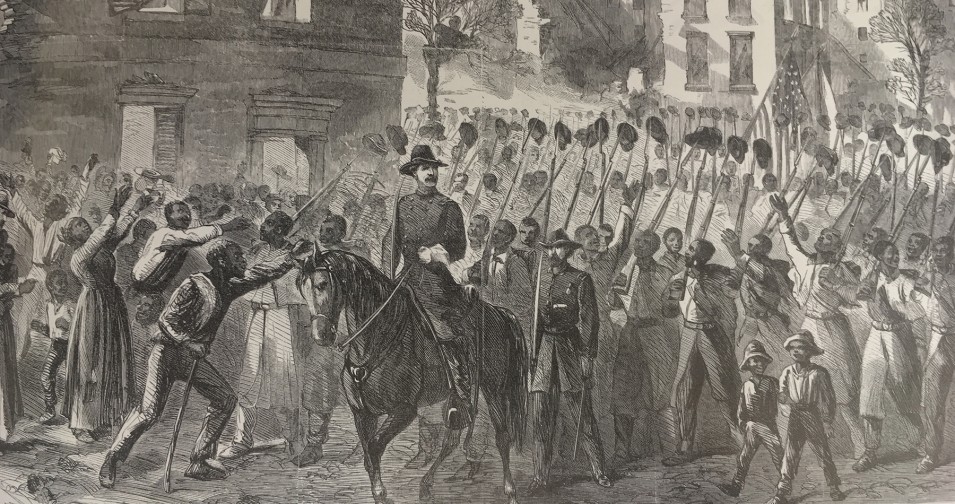

Hardee decided it was no longer feasible to defend Charleston with his diminished and battered troops. His forces evacuated on the night of February 17, 1865, and in the morning, the Union victors marched into a largely vacant city. Exultant black residents greeted them, cheering the end of slavery. A Union reporter entering Charleston described the scene: “The wharves looked as if they had been deserted for half a century. Broken down, dilapidated . . . the public buildings, we look at them and hold our breaths in utter amazement . . . all around the area of desolation are the ruined houses that still stand—Gillmore Town, as the Negroes call it.”

The war ended in May 1865, and residents, black and white alike, began the slow process of rebuilding and creating new lives in an era of profound change. William Middleton, a Charleston elite and Confederate soldier, stated, “There has been an utter topsy turveying of all of our dear institutions.” In the city, rents were high because so many properties had been destroyed or damaged by fires and shelling.

On Kiawah, despite foraging and skirmishes by both forces during the war, Vanderhorst Plantation survived with minimal damage, thanks to mulatto overseer Quash Stevens, who had guarded the house. Plantation owner Isaac Wilson was not so lucky. At his Shoolbred plantation, Confederates in retreat had “broken into the fine dwelling house and maliciously destroyed the furniture, and left the house in such a condition that it scarcely ever will be habitable for a decent family.”

The Vanderhorsts took oaths of allegiance to the United States in 1865 so they would be allowed to return to their property. Arnoldus Vanderhorst’s experience was typical of Lowcountry plantation owners: he enlisted and fought in the war, then came home to a desolate plantation and bankruptcy. In 1870 the whole of Kiawah Island only generated 385 bales of cotton, a fraction of the pre-War crop.

The U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau established offices throughout South Carolina to assist former slaves and to oversee labor relations between freedmen and former masters. Vanderhorst signed a contract agreeing to provide one hundred dollars a year and provisions of bacon, salt, corn, and clothing for workers who stayed at his plantation. Seven households remained, and by 1880 the plantation was turning a profit.

Federal Reconstruction continued until 1876, when South Carolina was left to its own political devices. It would take decades, or longer, to recover from the economic turmoil of the War. As the sesquicentennial of the end of the Civil War passed in 2015, South Carolinians remembered the negative aspects and positive changes resulting from the conflict. And one has only to walk along the Battery and look out to Fort Sumter to remember how fortunate it was that beautiful Charleston survived five years of war.